A single act of uniformity with the divine will suffices to make a saint. Behold while Saul was persecuting the Church, God enlightened him and converted him.

What does Saul do? What does he say? Nothing else but to offer himself to do God’s will: “Lord, what wilt thou have me to do” (Acts 9:6).

In return the Lord calls him a vessel of election and an apostle of the gentiles: “This man is to me a vessel of election, to carry my name before the gentiles”.

Absolutely true – because he who gives his will to God, gives him everything. He who gives his goods in alms, his blood in scourgings, his food in fasting, gives God what he has. But he who gives God his will, gives himself, gives is.

everything he

Such a one can say: “Though I am poor, Lord, I give thee all I possess; but when I say I give thee my will, I have nothing left to give thee.” This is just what God does require of us: “My son, give me thy heart” (Prov. 23:26).

St. Augustine’s comment is: “There is nothing more pleasing we can offer God than to say to him: ‘Possess thyself of us’”.

We cannot offer God anything more pleasing than to say: Take us, Lord, we give thee our entire will. Only let us know thy will and we will carry it out.

If we would completely rejoice the heart of God, let us strive in all things to conform ourselves to his divine will. Let us not only strive to conform ourselves, but also to unite ourselves to whatever dispositions God makes of us.

Conformity signifies that we join our wills to the will of God. Uniformity means more – it means that we make one will of God’s will and ours, so that we will only what God wills; that God’s will alone, is our will.

This is the summit of perfection and to it we should always aspire; this should be the goal of all our works, desires, meditations and prayers.

To this end we should always invoke the aid of our holy patrons, our guardian angels, and above all, of our mother Mary, the most perfect of all the saints because she most perfectly embraced the divine will.

The greatest glory we can give to God is to do his will in everything. Our Redeemer came on earth to glorify his heavenly Father and to teach us by his example how to do the same.

St. Paul represents him saying to his eternal Father: “Sacrifice and oblation thou wouldst not: But a body thou hast fitted to me…Then said I: Behold I come to do thy will, O God” (Habakkuk 10:5-7). Thou hast refused the victims offered thee by man; thou dost will that I sacrifice my body to thee. Behold me ready to do thy will.

Our Lord frequently declared that he had come on earth not to do his own will, but solely that of his Father: “I came down from heaven, not to do my own will, but the will of him that sent me” (John 6:38).

He spoke in the same strain in the garden when he went forth to meet his enemies who had come to seize him and to lead him to death: “But that the world may know that I love the Father: and as the Father hath given me commandment, so do I; arise and let us go hence” (John 14:31).

Furthermore, he said he would recognize as his brother, him who would do his will: “Whosoever shall do the will of my Father who is in heaven, he is my brother” (Matthew 12:50).

To do God’s will – this was the goal upon which the saints constantly fixed their gaze. They were fully persuaded that in this consists the entire perfection of the soul.

Blessed Henry Suso used to say: “It is not God’s will that we should abound in spiritual delights, but that in all things we should submit to his holy will.”

“Those who give themselves to prayer,” says St. Teresa, “should concentrate solely on this: the conformity of their wills with the divine will. They should be convinced that this constitutes their highest perfection. The more fully they practice this, the greater the gifts they will receive from God, and the greater the progress they will make in the interior life.”

A certain Dominican nun was vouchsafed a vision of heaven one day. She recognized there some persons she had known during their mortal life on earth.

It was told her these souls were raised to the sublime heights of the seraphs on account of the uniformity of their wills with that of God’s during their lifetime here on earth.

Blessed Henry Suso, mentioned above, said of himself: “I would rather be the vilest worm on earth by God’s will, than be a seraph by my own.”

During our sojourn in this world, we should learn from the saints now in heaven, how to love God. The pure and perfect love of God they enjoy there, consists in uniting themselves perfectly to his will.

It would be the greatest delight of the seraphs to pile up sand on the seashore or to pull weeds in a garden for all eternity, if they found out such was God’s will.

Our Lord himself teaches us to ask to do the will of God on earth as the saints do it in heaven: “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10).

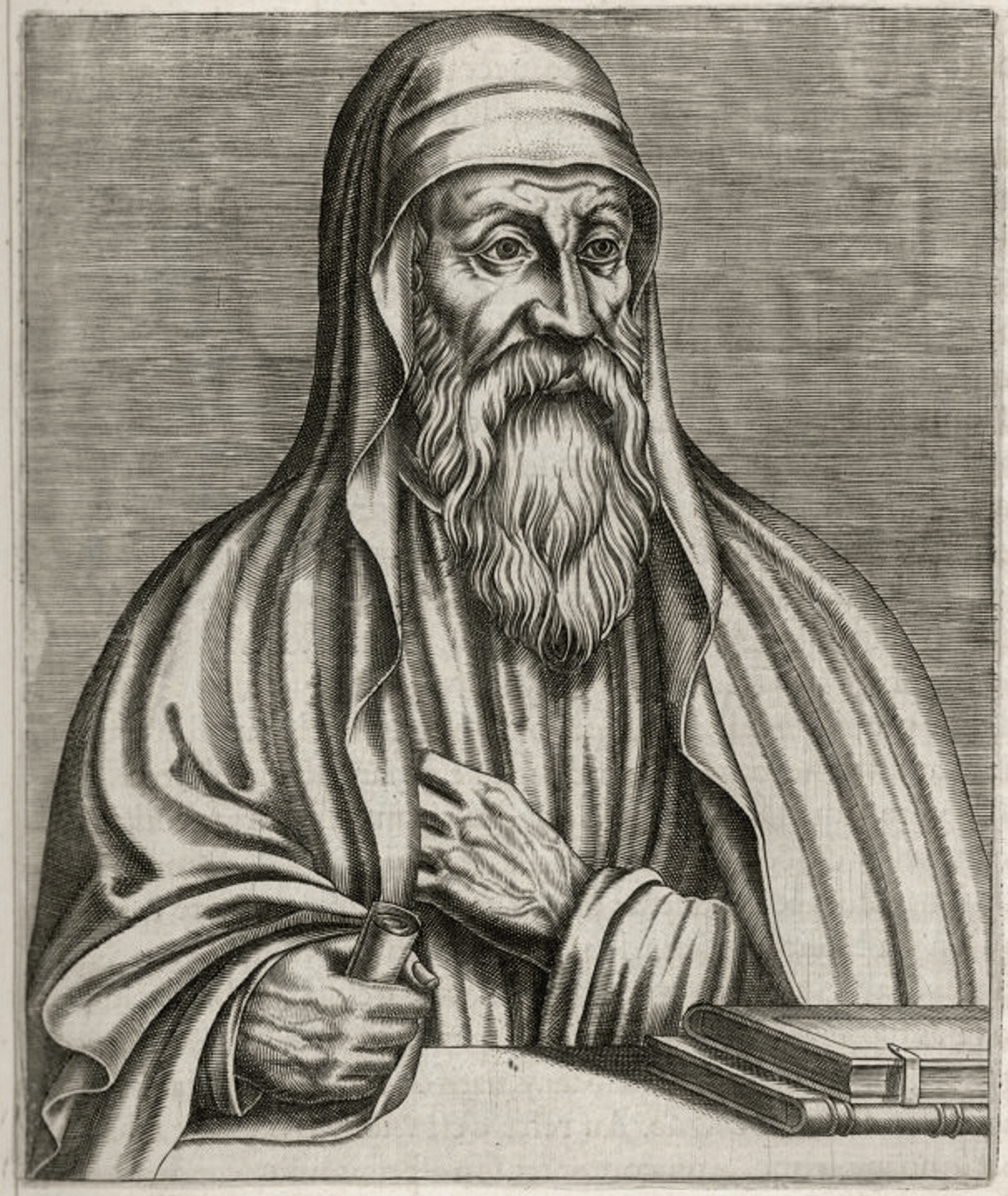

Alphonsus Liguori (1696-1787): Uniformity with God’s will